Brain Food #863: Studio Ghibli, AI, and the cost of efficiency

The hidden value of difficulty in the age of demystification

The Jevons Paradox suggests that tools and technological advancements that are designed to bring more efficiency into our lives end up having the opposite effect. Fuel efficiency gains increase fuel use, leading to an overconsumption of resources. More highways that fit more cars encourage more people to drive on them, leading to congestion. The introduction of domestic appliances increased work and decreased leisure time, often as a direct result of their maintenance or use—think of loading and emptying a dishwasher. Today, the natural suspicion, or conclusion, is that AI will have the same effect. Efficiency takes away barriers, and gives people the chance to do more of something, because it is now easy and accessible.

These past few days, the internet has been flooded with AI-generated visuals in the style of Studio Ghibli. The process is easy: you upload a photo to an AI tool and give it a prompt so it reproduces it in the iconic studio’s animation aesthetic. Beyond the ethical and legal implications of this—Is it pastiche? Is it plagiarism?—there is another question to consider. What is the cost of efficiency? Of obtaining something or getting something done easily, without friction?

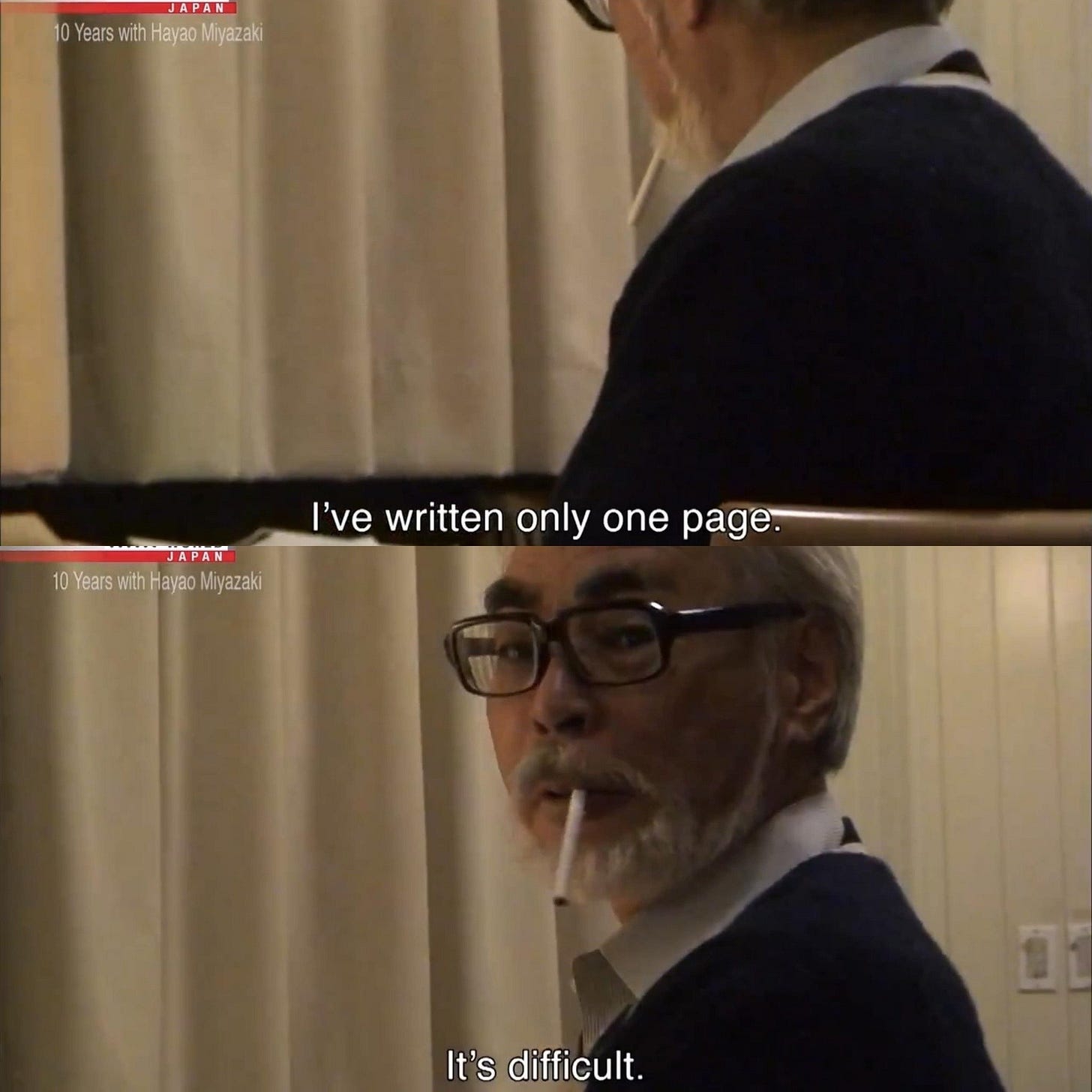

Studio Ghibli’s co-creator and mastermind, Hayao Miyazaki, is a great believer in the torture of the work. Like most creators, he is a perfectionist and, therefore, hard to please. His one-liners on being an artist are hilariously bleak. There is a moment in the documentary The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness where he says, “Over here is the chest I keep my hopes and dreams in.” He leans into it, facing away from the camera. “It’s empty.”

Miyazaki’s philosophy has been consistent: “Do everything by hand, even when using the computer.” Most Studio Ghibli productions are hand-drawn, with CGI used sparingly, despite the ease that new technologies brought to the creation of animation. Therein lies the hidden value in the difficulty of gaining something. Films like Princess Mononoke and Spirited Away are masterpieces, combining the magic of storytelling with the handcrafted nature of artistry. They are all the more impressive because they are hand-drawn, a rare combination of creative vision and mastery. They capture the value of time, something efficiency tools try to remove—the time taken to learn a craft, and the time taken to apply it.

Had it been hard to turn any image into a Studio Ghibli one, perhaps only a handful of people would have taken the time and made the effort to do it. Just because something is easy doesn’t mean it is worth trying. On the other end, the difficulty behind gaining or making something filters out greed, so only true desire remains. Roland Barthes said, “In order to show you where your desire is, it is enough to forbid it to you a little.” The harder something is, the more it reveals who really desires it.

If everything lies within our grasp, it loses its value:

“χαλεπά τα καλά

Chalepa ta kala.

The beautiful is beautiful.

The beautiful is noble.

The beautiful is difficult.It was possible for all three translations to be correct, because beauty, difficulty and nobleness were, for the Ancient Greeks, concepts not yet split apart.”

— from Han Kang’s Greek Lessons

In his 1917 essay ‘Art as Technique’, Russian critic Viktor Shklovsky wrote that art is valuable because it defamiliarises the familiar, and by doing so, it increases our difficulty of understanding and reawakens us to the mystery of being alive:

“Habitualisation devours work, clothes, furniture, one’s wife, and the fear of war […] And art exists that one may recover the sensation of life; it exists to make one feel things, to make the stone stony. The purpose of art is to impart the sensation of things as they are perceived and not as they are known. The technique of art is to make objects “unfamiliar,” to make forms difficult, to increase the difficulty and length of perception because the process of perception is an aesthetic end in itself and must be prolonged.”

As Miyazaki said to his CGI staff, a prompt we can apply to our own lives, “We're making a mystery here, so make it mysterious.”