Sometimes, I think about roads and maps. The purpose of roads is to provide a recognisable, reliable route from one point to another. The purpose of maps is to provide a sense of place and direction; to know what roads exist so we are able to navigate our surroundings.

Sometimes we follow a road only because it is there; someone created it and put it on the map.

Sometimes, doubt will ask us to take a step back, to assess our maps, reevaluate how true and helpful they are. Whether the roads they contain are the only ones that exist.

Without maps, we would be lost. Yet, we still need our own mental framework to help us navigate the territories of life. This creates a conflict: When there is a pre-existing path that we need to take, even if it wasn’t what we had in mind, do we question it, or do we stay on it?

In her memoir, Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal, Jeanette Winterson shares an anecdote from Gertrude Stein and Alice Toklas’ time during World War I, a moment of having doubt and being lost:

“Gertrude and Alice are living in Paris. They are helping the Red Cross during the war. They are driving along in a two-seater Ford shipped from the States. Gertrude likes driving but she refuses to reverse. She will only go forward because she says that the whole point of the twentieth century is progress.

The other thing Gertrude will not do is read the map. Alice Toklas reads the map and Gertrude sometimes takes notice and sometimes not.

It is going dark. There are bombs exploding. Alice is losing patience. She throws down the map and shouts at Gertrude: ‘THIS IS THE WRONG ROAD.'

Gertrude drives on. She says, ‘Right or wrong, this is the road, and we are on it.”

Sometimes, there is no choice, no right or wrong, especially when it comes to our own road. The road is simply the road. The only direction is forward.

The territory itself changes. Maps get outdated, and the complexity increases as all of us have constructed our very own maps as reference points. What remains is the reality of the situation—the road we find ourselves on.

Moving forward without reading the map carries a sense of carelessness, but also of defiance, in believing in the road itself and trusting the journey, even if we have no absolute control or knowledge of where the road will lead.

In his novel 1Q84, Murakami wrote: “I’m looking at a map and I see someplace that makes me think, ‘I absolutely have to go to this place, no matter what.’ And most of the time, for some reason, the place is far away and hard to get to.”

We may find that this destination is leading us back to ourselves. As German poet and philosopher Georg Philipp Friedrich Freiherr von Hardenberg wrote: “Where are we really going? Always home!”

His pen name was Novalis, which means ‘one who opens up new land.’

When there is doubt, when our maps are outdated, when the path looks difficult, the road of reality shows you where you need to go, sometimes even towards the difficulty itself. That is where new lands may be waiting to unfold.

Winterson’s anecdote is in a chapter that describes the aftermath of ejecting herself from the home she grew up in and heading out into the unknown. In an exchange with the local librarian, she asks, “Who was Gertrude Stein?” The librarian responds, “A modernist. She wrote with no regard to meaning.”

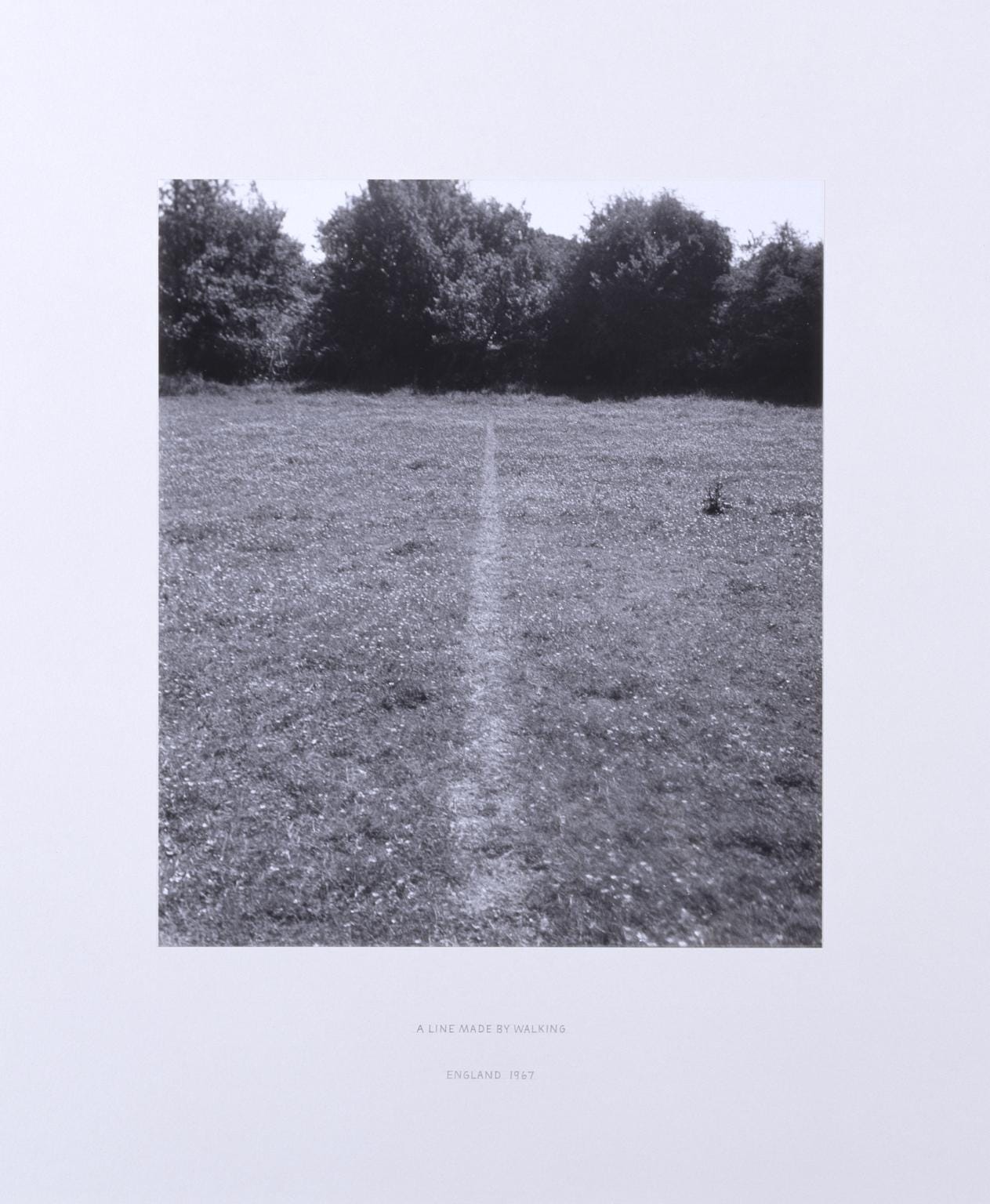

Once, roads didn’t exist, so we made them—like meaning, like stories. At the end of the day, meaning is constructed through our actions, the steps we choose to take along the journey, especially when the path is not certain.

Doubt and difficulties will make us question the road ahead. Hope will keep us on it. Sometimes, that hope comes from the reminder that the road itself once did not exist, until enough people walked that same route. Hope is a collective activity—if enough of us walk the same path, it becomes a road.

Hope is like a road in the country;

there was never a road,

but when many people walk on it,

the road comes into existence.— Chinese writer, Lin Yutang