There is power in saying yes to yes, in how it fosters openness through vulnerability, breaking us out of our safe yet stifling shells. But sometimes, hearing no is inevitable. Doors will close, paths will get erased, dreams will be deferred. A world is made out of the yes, but is not filled with it.

A no is, by default, exclusionary—it leaves us out of the story. But that could also be because that story wasn’t ours in the first place.

As Rilke wrote in The Beholder:

“Winning does not tempt that man.

This is how he grows: by being defeated, decisively,

by constantly greater beings.”

In his book Giving Up, despite the misleadingly defeatist title, British psychotherapist Adam Phillips outlines how the act of being left out can be a regenerative one:

“Exclusion may involve the awakening of other opportunities that inclusion would make unthinkable. If I’m not invited to the party, I may have to consider what else I want: the risk is that being invited to the party does my wanting for me, that I might delegate my desire to other people’s invitations. Already knowing, or thinking we know, what we want is the way we manage our fear of freedom. Wanting not to be left out may tell us very little about what we want, while telling us a lot about how we evade our wanting.”

After all, it is only when something is lost that most stories can begin. The fundamentals of storytelling suggest that every story starts with a character who wants something they can’t get.

“Once there has been an exclusion, a catastrophic loss, the story can begin. We only start out after being left out.”

Some decades earlier, the American psychoanalyst Allen Wheelis wrote about the importance of constraint in finding one’s freedom—perhaps the freedom Phillips suggests we tend to run away from by thinking we know what we want—in his book How People Change:

“For if he knows the constraint and nothing else, if he thinks ‘Nothing is possible,’ then he is living his necessity; but if, perceiving the constraint, he turns from it to a choice between two possible courses of action, then—however he choose—he is living his freedom. This commitment to freedom may extend to the last breath.”

In the lonely woods of Walden, Henry David Thoreau reflected on being lost as a way of being found:

“Not till we are lost, in other words, not till we have lost the world, do we begin to find ourselves, and realize where we are and the infinite extent of our relations.”

A ‘no’ does not necessarily have to be a blatant rejection; it may be internal, implicit, a realisation long in the making that some things may be out of reach or outside of our abilities. Not as some form of unfair cruelty by the world against us, but simply as nature taking its course. Not because of inferiority, but because of incompatibility.

There is something about the no that can invite us to change our perspective, steering us towards a more authentic life. As Phillips said, “When we are left out we become who we are, and who we can be.”

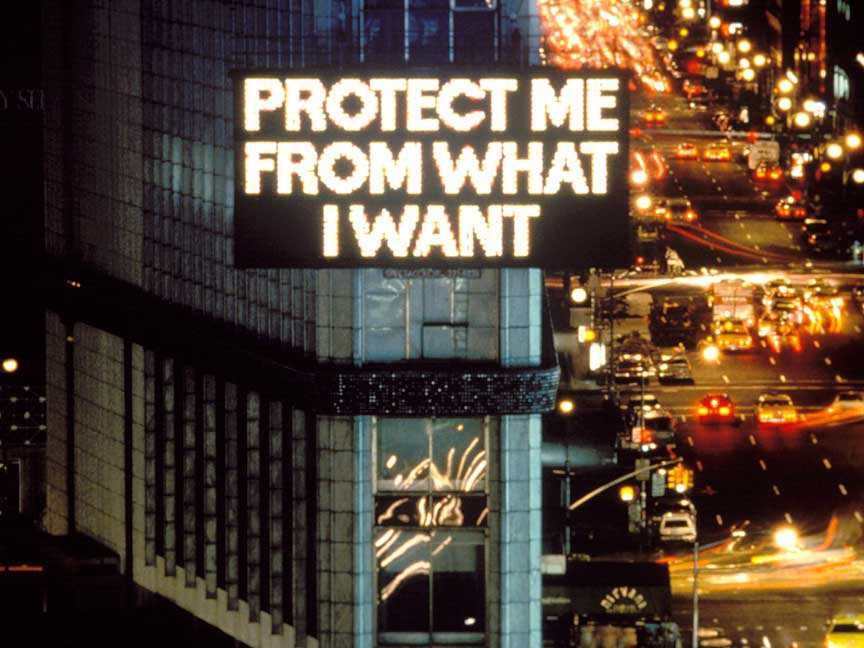

Jenny Holzer wanted to write but, not seeing herself as a real writer, she turned her texts into art. Tilda Swinton similarly went to Cambridge aspiring to be a poet, but soon found herself acting. Both exclusions were self-chosen and, eventually, shaped their artistic identities. Swinton elegantly summarised the paradox of feeling at home as an outsider: “It’s a real comfort zone for me to feel alien.”

It takes a while to see that the meandering road is actually a path.

I have had to save this off and reread to truly absorb the message. I think it’s a way of getting through these times we are having thrust upon us.