Brain Food #842: How things should be

What the length of a book can teach us about norms

Thoughts of the day

The average length of a novel is around 80,000 words, and any publishing guide will instruct aspiring writers to not even think of submitting anything that is under 70,000 words. The same goes for the other end of the scale, with extremely long books often being disfavoured, due to the potential challenges they might present both to their reader and their publisher.

What makes a ‘book,’ and why does it have to be a specific number of words, in the same way that a film or song also needs to be of a certain length? Who, or what, dictates how things should be?

As far as books go, the favourable length is the result of a complex combination of history and the changing availability of leisure time, plus production costs, and market needs. All of these come together to form conventions and labels; perhaps it was the same inertia that initially prevented Van Gogh’s work from being accepted as art.

Haruki Murakami, one of the most prolific Japanese writers of the present day, revealed how he tried to free himself from such limitations:

“Give up trying to create something sophisticated. Why not forget all those prescriptive ideas about ‘the novel’ and ‘literature’ and set down your feelings and thoughts as they come to you, freely, in a way that you like?”

Novels like In Search of Lost Time or Ulysses broke conventions when they were first published, through their length but mostly through their narrative format. They are considered modern classics today.

Mrs Dalloway is 63,000 words long, which would have placed it below today’s acceptable word count for published novels. The book has no chapters, only section breaks to denote the passing of an hour, since the entire plot takes place over a single day. It began its life as a short story, Mrs Dalloway in Bond Street, but then grew into something else (a reminder that starting small can be the beginning of something great). As writer Hisham Matar suggested, referring to Virginia Woolf’s masterpiece, less is not necessarily more; it is simply enough:

“So one does not need the epic. You can do as much, perhaps more, with as little as two characters and a day. And you no longer cast your net in order to catch the whole sea. Instead, you angle for the one perfect fish.”

Some conventions can be seen as foundations for experimentation. There are rules that become laws, and then there are rules that are unwritten, embedded in our thinking as norms. Like fiction itself, or any form of narrative, some conventions can be purely deceiving, and when followed too strictly they might kill creativity and opportunity. The rules of success, happiness, of what makes a life fulfilling. And like the story of the four-minute mile, ‘It can’t be’ or ‘It can’t be this way’ may be a temporary status, much like everything else.

This thinking can be applied to multiple areas of life. Once you question why some things are the way they are (for example, having three meals a day, the length of a working day or week, owning a car) there might not be an immediately obvious answer.

Status quo bias is the human tendency to lean towards the familiar. But nothing new was discovered by staying put. Sometimes, all that is needed is a new perspective.

From Anne Carson’s The Glass Essay:

This is a coded reference to one of our oldest arguments,

from what I call The Rules Of Life series.

My mother always closes her bedroom drapes tight before

going to bed at night.I open mine as wide as possible.

I like to see everything, I say.

What’s there to see?

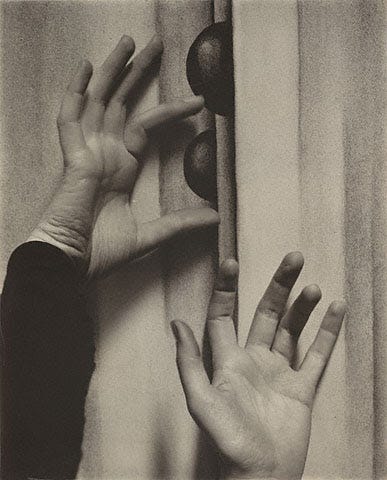

Art movements like Dadaism and Pop art challenged traditional views of art, even what art itself is. Today, they are accepted as significant parts of art history. But perhaps the best example is photography, invented in 1822, but not considered fine art until the early 1900s, when Alfred Stieglitz introduced it into art galleries — in fact, the very one that he opened himself.

Stieglitz founded The Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession in 1905, which then became 291, the central platform for non-traditional media and avant-garde art in New York, and subsequently the US.

We can let the norms define how things should be, or we can decide ourselves.

Thank you for reading today’s Brain Food. Brain Food is a short newsletter that aims to make you think without taking up too much of your time. If you know someone who would like this post, consider spreading the word and forwarding it to them. Brain Food wouldn’t exist without the support of its readers.

And if you have just come across Brain Food, you can subscribe to it below: