Brain Food #836: The lightness of paper, the heaviness of stone

Louise Bourgeois on the fleetingness of thought and the exorcism of sculpture

Thoughts of the day

Louise Bourgeois, who was in psychoanalysis for decades, a process that started in 1951 and only ended with the death of her analyst in 1985, was an artist that often excavated her own soul for hidden meaning. This, in turn, led to much of her art, from steam-of-consciousness scribbles on paper to giant motherlike sculptures of spiders.

Less known was her writing, much of which was discovered and made public after her death (whether she intended for this to be seen by others will remain a mystery). In her words, she often refers to and extends her analysis, but also sheds light on her views on what it means to make art, the lightness of paper, and the heaviness of stone.

Similar to Milan Kundera, she touches on how everything is impermanent and singular. Even in drawing or writing, something more accessible and faster than sculpture, and perhaps the closest one can get to having a tool that can capture a thought or feeling, by the moment it is put on paper, its original form is gone forever.

For Bourgeois, drawing remains one of the most reliable means of recording life’s fleetingness, the lighter and more irrational parts of one’s psyche:

“Drawings have a featherlike quality. Sometimes you think of something and it is so light, so slight, that you don’t have time to make a note in your diary. Everything is fleeting, but your drawing will serve as a reminder; otherwise it would be forgotten. This applies sometimes to fears. You fear something, yet you hardly notice it–as if someone were walking there in the distance, or a cat were to jump out on the terrace. I talk about fears, but you could talk about other subjects. For instance you could talk about the notion of pleasure. Something that you see over there gives you intense pleasure. Somebody of the opposite sex, right? Just a glance, but you cannot say that it doesn’t have an effect on you, because if you said that I would say you were not telling the truth. It can be very fleeting. It hits you for just a few seconds and then, if you are married or something, you think of something else.”

But it is precisely in the act of making that a form of release happens; otherwise, as many in coaching circles say, when something is not expressed, it calcifies.

Sculpture, on the other hand, is described as a form of exorcism, a means of forgetting:

“Exorcism is necessary when the guilt has come in and you want to forget about it. You want to forget about certain experiences because they are forbidden. Sculpture needs so much physical involvement that you can rid yourself of demons through sculpting. Drawing doesn’t have that pretension. Drawing is just a little help.”

In the end, making something is rarely for someone else to see, but to be able to see oneself. Like the moment Tereza sees herself in the mirror, as if for the first time, in The Unbearable Lightness of Being:

“It was not vanity that drew her to the mirror; it was amazement at seeing her own ‘I.’ She forgot she was looking at the instrument panel of her body mechanisms; she thought she saw her soul shining through the features of her face. She forgot that the nose was merely the nozzle of a hose that took oxygen to the lungs; she saw it as the true expression of her nature.”

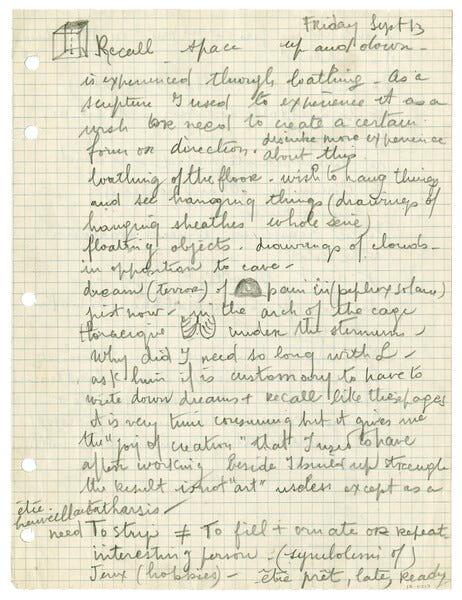

A page of Bourgeois’ writing, where she questions the purpose of recording memories and dreams, until she answers her own question: “it is is very time consuming but it gives me "the “joy of creation” that I used to have.”

I write Brain Food out of my own desire and willingness to share what I find interesting and to inspire others, and help them see life in a different light. All of Brain Food is free, but if you would like to subscribe or pledge your support of my work by committing to a future paid subscription you can do so below: