Brain Food #811: Consciousness, routines and compassion

'What the hell is water?'

Thoughts of the day

In Friday’s post, I wrote about how consciousness may be what still set humans apart from artificial intelligence. But there is also a downside to consciousness, particularly the form of extreme consciousness that arises from being limited, for a lifetime, to witnessing the world solely through our own existence; a form of solipsism that narrows our worldview to the belief that the only truths are the ones that exist in our mind.

I recently revisited David Foster Wallace’s infamous and celebrated commencement speech, titled This Is Water. Wallace starts his speech with the tale of two young fish that are not aware they are surrounded by water, because that is all the fish have ever known:

“There are these two young fish swimming along and they happen to meet an older fish swimming the other way, who nods at them and says ‘Morning, boys. How’s the water?’ And the two young fish swim on for a bit, and then eventually one of them looks over at the other and goes ‘What the hell is water?’”

What this implies is that consciousness does not equal awareness. Consciousness is a form of awareness, that of our own being, but awareness also requires an understanding of what is around us. With only the former, we might also be blind to the water that surrounds us:

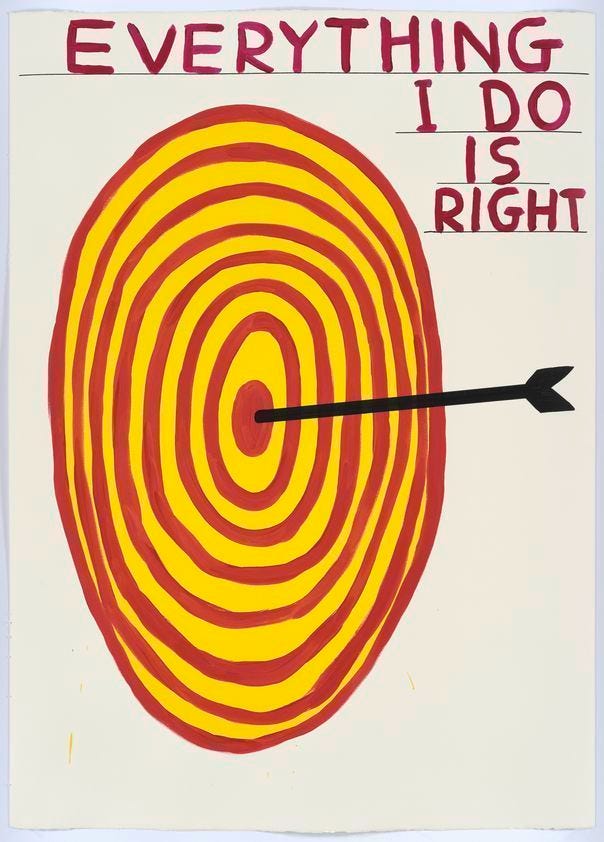

“Here is just one example of the total wrongness of something I tend to be automatically sure of: everything in my own immediate experience supports my deep belief that I am the absolute centre of the universe; the realest, most vivid and important person in existence. We rarely think about this sort of natural, basic self-centredness because it’s so socially repulsive. But it’s pretty much the same for all of us. It is our default setting, hard-wired into our boards at birth. Think about it: there is no experience you have had that you are not the absolute centre of. The world as you experience it is there in front of YOU or behind YOU, to the left or right of YOU, on YOUR TV or YOUR monitor. And so on. Other people’s thoughts and feelings have to be communicated to you somehow, but your own are so immediate, urgent, real.”

What disciplines like art, literature, philosophy, and psychology teach us, is that the human condition is universal, and very resistant to change. We are still largely, and unknowingly, driven by our instincts. The emotions we are able to feel are likely to be very familiar to a complete stranger. The world operates in a cyclical manner because the world is made of us.

A good story, particularly a good book that lets us into the thoughts of characters, can teach us compassion, by literally allowing us to read minds, and enabling us to view the world through the eyes of another. Most often, we learn that the universe is, in fact, not out to get us. Most Shakespearean plays remind us that we are creatures of our own doing, while the cosmos remains largely indifferent.

And so, the key to preventing consciousness from turning into self-centredness can be compassion, paired with communication, and pausing to take a frequent look at the things we take for granted, while asking ourselves why that is so.

If you have some time to spare this Monday, before fully immersing yourself in the cycle of another week, you can read one of the most mind-altering passages from the speech, on the time trap and thinking opportunities of routines, and the power of compassion:

“The point is that petty, frustrating crap like this is exactly where the work of choosing is gonna come in. Because the traffic jams and crowded aisles and long checkout lines give me time to think, and if I don’t make a conscious decision about how to think and what to pay attention to, I’m gonna be pissed and miserable every time I have to shop. Because my natural default setting is the certainty that situations like this are really all about me. About MY hungriness and MY fatigue and MY desire to just get home, and it’s going to seem for all the world like everybody else is just in my way. And who are all these people in my way? And look at how repulsive most of them are, and how stupid and cow-like and dead-eyed and nonhuman they seem in the checkout line, or at how annoying and rude it is that people are talking loudly on cell phones in the middle of the line. And look at how deeply and personally unfair this is.

[…]

But most days, if you’re aware enough to give yourself a choice, you can choose to look differently at this fat, dead-eyed, over-made-up lady who just screamed at her kid in the checkout line. Maybe she’s not usually like this. Maybe she’s been up three straight nights holding the hand of a husband who is dying of bone cancer. Or maybe this very lady is the low-wage clerk at the motor vehicle department, who just yesterday helped your spouse resolve a horrific, infuriating, red-tape problem through some small act of bureaucratic kindness. Of course, none of this is likely, but it’s also not impossible. It just depends what you want to consider. If you’re automatically sure that you know what reality is, and you are operating on your default setting, then you, like me, probably won’t consider possibilities that aren’t annoying and miserable. But if you really learn how to pay attention, then you will know there are other options. It will actually be within your power to experience a crowded, hot, slow, consumer-hell type situation as not only meaningful, but sacred, on fire with the same force that made the stars: love, fellowship, the mystical oneness of all things deep down.”

Thank you for reading today’s Brain Food. Brain Food is a short newsletter that aims to make you think without taking up too much of your time. If you know someone who would like this post, consider spreading the word and forwarding it to them. Brain Food wouldn’t exist without the support of its readers.

And if you have just come across Brain Food, you can subscribe to it below:

For longer thoughts and Brain Food highlights from the archives, visit Medium.